Community-guided research explores new tool to spot signs of PFAS in everyday products

New pilot project explores how a portable tool—and community input—can help identify toxic “forever chemicals” in the products we use every day

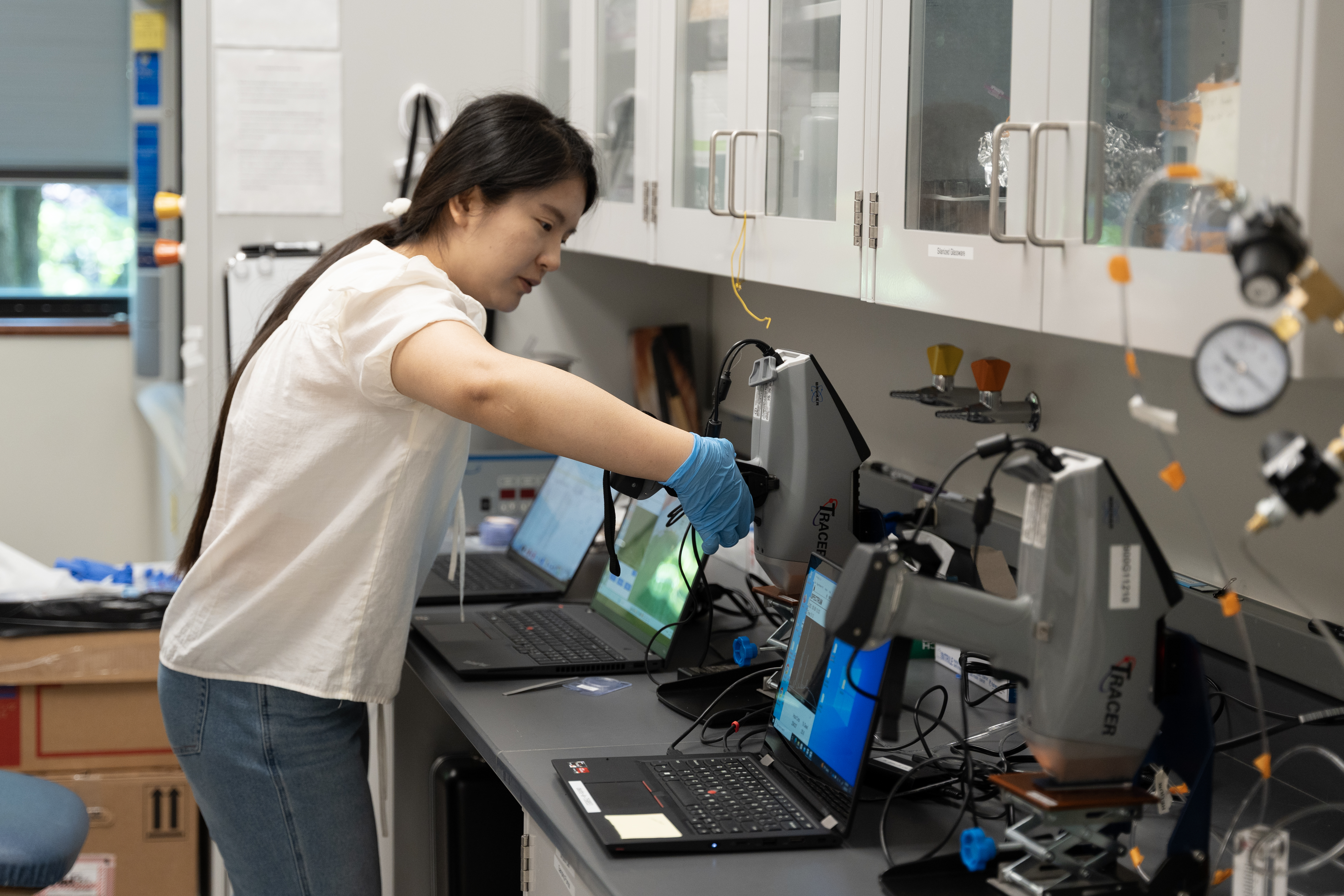

The Hazardous Waste Management Program, in partnership with the University of Washington, Public Health – Seattle & King County, and Purdue University, is taking bold steps to better understand PFAS exposure in our homes and communities. This first-of-its-kind pilot project, led by UW researchers, used a handheld screening instrument to test everyday items for signs of PFAS—long-lasting, harmful chemicals linked to cancer, immune suppression, and hormone disruption.

This project was funded through the Washington State Legislature as part of the 2023–2024 supplemental budget and reflects our shared commitment to preventing toxic exposures through innovation, science, and community engagement.

Why This Matters

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are found in many household products—nonstick pans, raincoats, takeout packaging—and don’t break down naturally if they leach into the environment. Over time, they can build up in our bodies and are associated with serious health risks, even at low levels.

Current methods for PFAS testing are costly, time-intensive, and must be performed in a lab. Products are also often destroyed during the testing process. These factors make it difficult to screen products for these harmful chemicals during community events or in-home investigations.

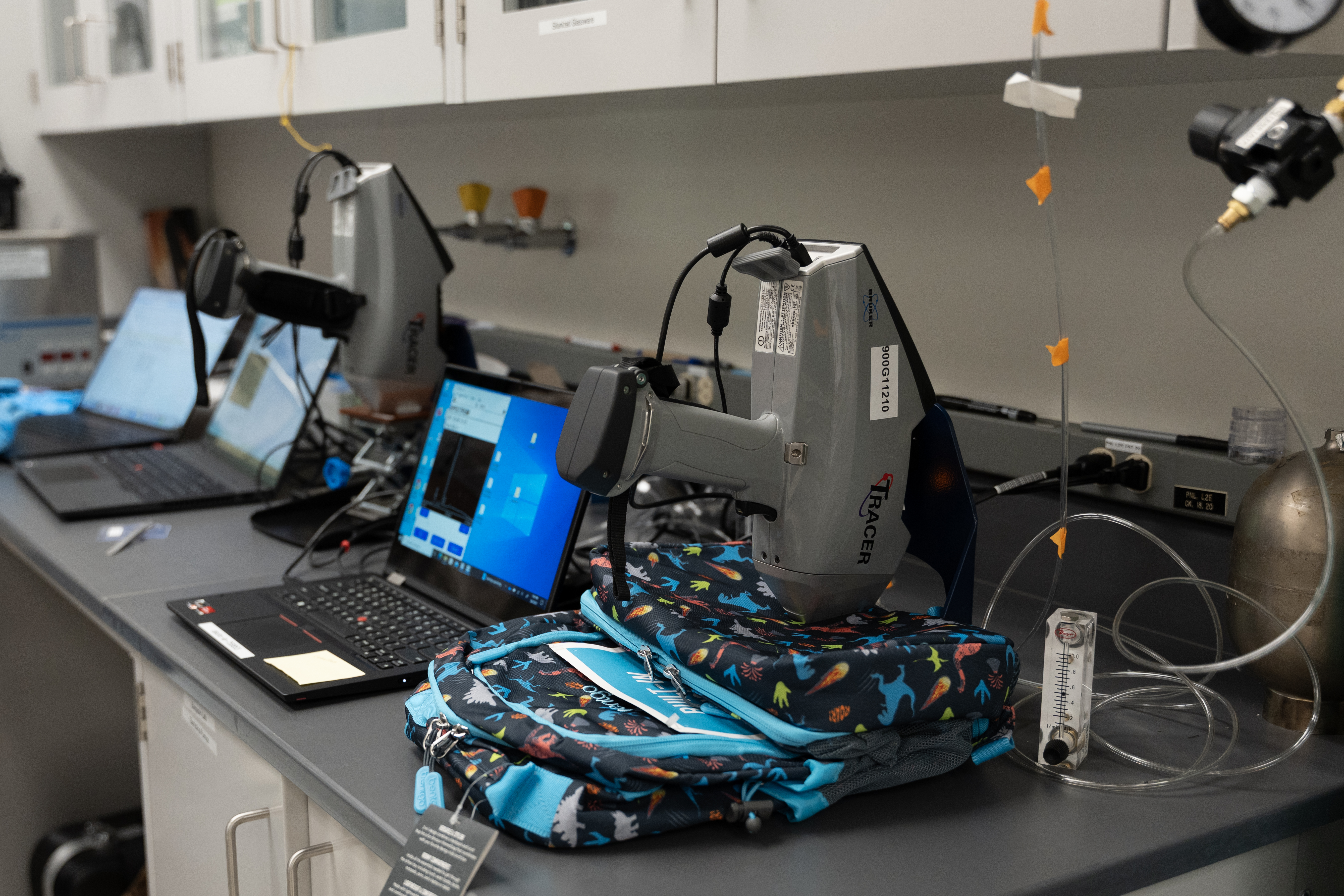

This pilot project explored a faster, portable, and more accessible screening option using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) device. XRF machines are handheld scanners that are used to test materials for the presence of certain elements like lead. For this research, the handheld scanner detected fluorine—a marker that may indicate the presence of PFAS in consumer products.

Through this pilot project, researchers found that the handheld XRF instrument performed well when evaluating items with high levels of fluorine, such as nonstick pans or waterproof jackets.

The researchers say these results are the first step toward developing a quicker and more accessible screening tool, but they note that additional research and refinements are needed to improve the accuracy of the process.

“We’re seeing the potential of this method to support community-level prevention,” said Trevor Peckham, Environmental Scientist at the Hazardous Waste Management Program. “It’s not a replacement for lab analyses, but it’s a meaningful step forward.”

A Community-Guided Approach

Critically important to this project design was the involvement of community voices from the start. Together, the Haz Waste Program, Public Health – Seattle & King County, and UW researchers worked with trusted community-based organizations to understand which products community members wanted to prioritize for testing. This important step informed which products were selected for testing and ensured that the findings were relevant to communities.

A bilingual poll (in English and Spanish) invited residents to rank products across five categories:

- Children’s products (e.g., toys, pacifiers)

- Cosmetics and personal care (e.g., lipstick, dental floss)

- Household items (e.g., nonstick cookware, carpet)

- Clothing and apparel (e.g., waterproof jackets)

- Food containers and packaging (e.g., wrappers, disposable coffee cups)

Products were selected based on community input, scientific literature, state and international regulations, and their likelihood to contain PFAS or come into contact with sensitive populations—especially children.

“Communities are asking important questions about chemical safety—and this project gave us a chance to listen, learn, and respond together,” said Shirlee Tan, Environmental Health Scientist at Public Health – Seattle & King County. “It’s a public health approach grounded in partnership.”

What We Found

Many of the items prioritized through community engagement contained high levels of fluorine. These items include:

- Rain jackets

- Eye shadow and foundation

- Nonstick cookware

- Some food packaging items

While fluorine detection alone doesn’t confirm PFAS, it raises a red flag—and helps public health professionals focus more detailed testing where it’s most needed.

“Because PFAS are commonly used in coatings, we prioritized items that come into contact with hands or mouths—especially for children—due to the increased risk of ingestion,” said Diana Ceballos, UW Assistant Professor and lead of the project. “With further refinement, the XRF fluorine method could offer health departments a practical, low-cost, and non-destructive screening tool to identify high-fluorine products in communities that cannot afford laboratory testing.”

What’s Next—and What It Means for You

This pilot supports broader efforts to make science and prevention more accessible across King County. The findings are already helping shape:

- Community outreach and product education

- Campaigns for safer alternatives

- Local toxics policy and prevention work

- Future testing strategies that prioritize equity and public health

“We’re proud to be part of this groundbreaking work,” said Maythia Airhart, Director of the Hazardous Waste Management Program. “It’s not just about detecting harmful chemicals—it’s about helping families make informed choices, sharing science in ways that are accessible, and building trust in the process.”

This project reflects the values our Program has upheld for 35 years: prevention, partnership, innovation, and centering the communities most affected by toxic exposures.

What You Can Do

Whether you’re just starting to learn about PFAS or already following the science, here are steps you can take:

Check Labels

PFAS are often found in products labeled:

- “Waterproof”

- “Stain-resistant”

- “Grease-repellent”

- “Nonstick”

- “Wrinkle-free”

Look out for ingredients that contain the words “fluoro-,” or “polyfluoro-.” These terms can be included in the beginning, middle, or end of an ingredient’s name.

Choose Safer Products

Opt for PFAS-free brands, untreated fabrics, stainless steel or cast-iron cookware, and cosmetics with clear ingredient labels and fewer ingredients.

It’s important to note, however, that manufacturers are not required to disclose if PFAS are included in their products. Labels like “eco-friendly,” “non-toxic,” and “green” mean very little without specifics or third-party product certification. This further underscores the importance of developing more accessible and cost-effective testing methods.

Know the Risks

PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because they break down over hundreds to thousands of years in the environment. They build up in our bodies over time and are linked to cancer, hormone disruption, altered immune responses, and other health effects—even at low levels.

Visit King County’s PFAS Hub for a quick primer and helpful tools.

Multimedia

Photo Gallery: See the project in action

Watch: B-roll: Behind-the-scenes lab testing video

Learn More

[PFAS Proviso Report (2025)]

[King County PFAS Hub]

[WA State Department of Ecology – PFAS Center]

About the Project

This research was led by the University of Washington Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences in partnership with:

- Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County

- Public Health – Seattle & King County

- Purdue University

Funded through the Washington State Legislature (Proviso 5950-SL, 2023–2024 Supplemental Budget).

Translate

Translate