History of our mission

Learn how King County's regional wastewater treatment system was created.

In the 1950s, wastewater flowed into Lake Washington and Puget Sound and many rivers and smaller lakes without enough treatment, fouling water and making a sullied mess of local beaches.

In 1958 the voters created Metro and developed a regional wastewater treatment system based on watersheds as opposed to political boundaries.

Shortly after Metro was formed, construction began on the county's two existing regional treatment plants, West Point in Seattle's Magnolia neighborhood and South Treatment Plant in Renton, which were officially up and running by 1966. By the late 1960s, regional water quality began improving dramatically.

In 1994, King County assumed authority of Metro and its legal obligation to treat wastewater for 34 local jurisdictions and local sewer agencies that contract with King County.

The early days of sewage and treatment disposal

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, the chief engineer for the City of Seattle, R. (Reginald) H. Thomson, led the design and construction of the city's sewer system. In planning the system for future growth, Thomson designed a brick sewer 12 feet in diameter across the north end of Seattle that went beyond needs of the time. Some huge sewer lines he designed are still in use today.

But back in Thomson's time, sewage treatment was not an issue. So the North Trunk Sewer discharged untreated sewage into Puget Sound. Finished in 1918, it reached Puget Sound at the base of the bluff at West Point. A dam blocked the lower half of the sewer line where it came through the bluff, but a smaller pipe exited the dam.

Outfall for sewage on Seattle's Magnolia Bluff, 1932.

Source: Seattle Municipal Archives, Item No: 38497

In the mid-1950s, the pipe carried 40 million gallons a day of city sewage through an outfall that ended a short distance offshore, about 25 feet deep. At any tide, the sewage caused a fan-shaped stain in the water of Puget Sound that was easily seen from the air.

At certain tides, the sewage washed aback onto shore. When it rained hard, sewage spilled over the dam in the North Trunk Sewer and spread across the beach. The sandy spit was coated with a dark slime, and health official closed nearby beaches because of bacterial contamination. And above West Point was Fort Lawton, a U.S. Army base, which prohibited public access to the West Point beach.

Throughout the Seattle-King County region in those days, only about 47 percent of all sewage got any treatment. Sixty outfalls discharged untreated waste into the Duwamish Waterway, Elliott Bay and Puget Sound.

And around Lake Union, Green Lake and Lake Washington, sewers carrying a combination of sewage and stormwater overflowed in rainy weather, contaminating those lakes and often forcing closure of swimming beaches.

As population grew in communities surrounding Lake Washington, 10 small sewage-treatment plants discharged 20 million gallons of effluent into the lake daily. Although the plants provided secondary treatment, scientists in the early 1950s began suspecting their phosphorus-rich effluent was damaging the lake. The effluent stimulated the growth of algae that deprived the lake of light and consumed oxygen from the water.

That led to a decline in water transparency. Green scum could often be seen on the lake surface, and in summer the unpleasant odor of dying algae was in the air.

Birth of Metro

The story of the wastewater treatment utility now serving the Seattle-King County region began in 1956 when a group of local residents became concerned about the effect of rapid urban growth, especially the decline of Lake Washington.

These conditions - and other regional concerns -- prompted citizens to begin a three-year study of metropolitan problems. Because of this study, citizens proposed a state law that would allow local government in Washington to form metropolitan federations.

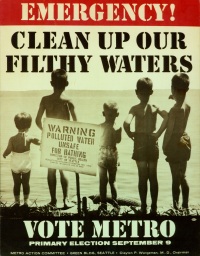

1958 Metro campaign poster

Called metropolitan municipal corporations, those federations could solve problems that crossed over the boundaries of cities, counties and special districts. In 1957, the state Legislature passed this measure by one vote on the last day of the session.

At the urging of the citizens committee, a ballot measure to establish the Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle was placed before voters in spring 1958. This measure would have given the agency responsibility for water pollution control, public transportation and comprehensive planning within its boundaries. The proposal passed within Seattle but failed in some suburban areas.

The citizen activists came back to organize a second effort, this time directed at solving the most pressing problem of the area: water pollution. This measure was placed on the ballot in the fall 1958. Endorsements came from both major political parties, the county commissioners, mayors of all 11 incorporated cities in the metropolitan area and all major civic groups.

The result, on Sept. 9, 1958, was an election victory and the birth of Metro. The measure got a 58 percent yes vote in Seattle and 67 percent in suburban areas.

Less than a year later, Metro would earn Look magazine's All-America City Award, even before the agency poured concrete or treated sewage. The honor was not for improving water quality but for "progress achieved through intelligent citizen action."

Planning the system

The first meeting of Metro's governing body, the Metropolitan Council, took place in October 1958. Originally, the Metro Council had 16 members and included elected officials from Seattle, King County and smaller cities. When the state Legislature enlarged boundaries of Metro in 1971, the council expanded to 36 members.

In the 1980s, more representatives from the City of Bellevue, sewer districts in the Metro service area, and unincorporated areas brought the total to 40 members.

Metropolitan Seattle Sewerage and Drainage Survey, March 1958

The council's first major action was to adopt the Comprehensive Sewage Plan. The major elements of this plan had been prepared before the election as a joint effort by the state, King County and the City of Seattle. The plan called for removing all treatment plant discharges from Lake Washington and abandoning all 10 small treatment plants on its shores.

Under the plan, Metro would build four wastewater treatment plants--at Renton, West Point, Carkeek Park and Richmond Beach. Metro would take over operation of the City of Seattle's new sewage treatment plant at Alki beach. And Metro would build large interceptor sewer lines around Lake Washington, on the Duwamish Waterway and along Seattle's commercial waterfront, Elliott Bay.

Metro opened its first office on June 1, 1959. On May 4, 1961, it published its first call for construction bids-for the Richmond Beach and Carkeek Park treatment plants.

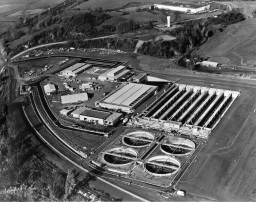

Groundbreaking for the construction program took place on July 20, 1961, at the site of the Renton Treatment Plant, now called the South Treatment Plant. The secondary treatment plant would be built on 53 acres bought from the Great Northern Railroad and the Earlington golf course. In its first phase, the plant would treat an average dry-weather flow of 24 million gallons a day.

And on July 1, 1962, Metro took over operation of all treatment plants, major trunk sewers and pump stations within its boundaries.

Building regional facilities

Challenging problems faced engineers as Metro's sewer construction program got under way. Hilly terrain, high water tables and Lake Washington itself were a few of the obstacles.

Renton Treatment Plant (under construction, 1963)

West Point Treatment Plant Dedication, July 20, 1966

Crews built miles of tunnels with sections up to 18.5 feet in diameter. To move sewage from the Kenmore area to a new Matthews Beach pump station in north Seattle, Metro built a 7-mile-long pipeline underwater pipe along the shore of Lake Washington. The pipe, supported by concrete pilings, was built offshore to avoid tearing up neighborhoods. From Matthews Beach, Metro built a 3.3-mile sewer tunnel to Seattle's old North Trunk sewer in the University District.

By the end of the first 10-year construction program, Metro had built dozens of wastewater pump stations and more than 100 miles of large trunk lines and interceptor sewers.

During this period, Metro finished its wastewater treatment plants. In July 1962, Metro dedicated the small Carkeek Park Treatment Plant, and in October that year, Metro acquired the West Point beach from the U.S. Army. In February 1963, the first treatment plant effluent was diverted from Lake Washington to a new interceptor sewer. And in April that year, the Richmond Beach Treatment Plant was finished.

On July 22, 1965, the Renton Treatment Plant was dedicated. And on July 20, 1966, citizens, dignitaries and Metro employees gathered to celebrate the dedication of the West Point Treatment Plant. On March 30, 1967, the Lake City Treatment Plant was closed, ending the flow of effluent into Lake Washington less than nine years after Metro was formed.

Seattle attorney James R. Ellis, who inspired and led the campaign to create Metro, saluted volunteers and called for a dedication to further advances against environmental abuse in an eloquent, definitive speech at the dedication of the West Point plant.

The cost of construction under the 10-year sewerage plan was $125 million. In fact, the construction cost for the first stage was only 2 percent over the 1961 estimate. Metro paid for construction by selling revenue bonds to be repaid by monthly sewer bill receipts.

The Metro Council decided to follow a voluntary program for connecting local systems to the metropolitan sewer system. Eventually, all municipal utilities and sewer districts within the Lake Washington and Green River watersheds entered standard contracts with Metro for wastewater treatment.

Metro has never directly billed individual property owners for sewer service. Instead, it bills cities and sewer districts a wholesale rate based on the number of customers they serve, and those agencies collect Metro's fee as part of their regular sewer billing.

Local money paid all but 4 percent of the total cost of Metro's construction program. Area residents not only undertook an innovative effort to form Metro, but they also paid for the system themselves. Very little federal money was involved in the first 10-year construction program.

Getting results

Completion of the major sewage-treatment facilities brought dramatic results. Effluent, which at one time entered Lake Washington at 20 million gallons a day, was reduced to zero discharge in February 1968. The lake transparency, as low as 30 inches in 1964, was 10 feet by 1968.

The five grown children of Robert and Dorothy Block gather on the shore of Lake Washington to recreate a 1958 Metro campaign photo. Robert and Dorothy Block co-chaired the citizen committee effort. Above photo taken in 1988.

By 1977, Lake Washington was clearer than ever before in its recorded history.

Water quality elsewhere along Seattle's waterfront also improved dramatically. In 1970, after the city closed its Diagonal Avenue Treatment Plant and Metro completed its Elliott Bay interceptor sewer, dissolved-oxygen levels in the Duwamish Waterway estuary soared from a low of three-tenths of a milligram per liter to more than 4 milligrams per liter. The result: a healthier environment for marine life.

The Elliott Bay interceptor sewer system made Seattle's commercial waterfront one of the cleanest in the world. Underwater surveys and lab analysis of water samples from West Point showed similar improvements after the new plant ended the flow of raw sewage onto the beach.

The Metro Council adopted plans for the second stage of the construction program in 1970. This part of the plan called for changes and additions needed to meet water quality requirements of regulatory agencies, enlargement of facilities, and expansion to provide service to new areas.

Following Metro's success in improving water quality, the state Legislature in 1971 passed a citizen-sponsored bill allowing Metro to levy a 0.3 percent addition to the sales tax to pay for public transit if local citizens approved. The Legislature had earlier authorized a local motor-vehicle excise tax to pay for public transportation systems in communities that also levied local matching taxes for transit.

In September 1972, voters authorized-with a 58 percent vote-a Metro-operated countywide public transit system and the levy of an additional sales tax. Every legislative district in the county voted for that historic step.

In 1985, Metro finished a major expansion of its Renton plant (now called the South Treatment Plant), doubling the plant's capacity to 72 million gallons a day.

Metro also finished a 12-mile underground pipeline in 1987 designed to protect the Duwamish Waterway. Treated wastewater from the Renton plant was diverted from the Duwamish to this pipeline for discharge into Puget Sound off Duwamish Head. That diversion almost eliminated ammonia in the river, and oxygen levels in the river improved significantly.

The American Consulting Engineers' Council gave its Award of Engineering Excellence to Metro in 1987 for engineering design of the Renton effluent transfer system.

Another major construction project ended in 1987 when Metro opened its state-of-the-art Environmental Laboratory on the Lake Washington Ship Canal. Now operated by the Water and Land Resources Division in King County's Department of Natural Resources and Parks, the lab monitors and analyzes environmental data for use in the regional, comprehensive water quality plans.

In 1989, Metro earned the American Public Works Association designation for a Project of Historical Significance for cleanup of Lake Washington, 1959-1989.

Operating water quality programs

In 1972, the U.S. Congress passed sweeping amendments to the federal Water Pollution Control Act that greatly affected Metro's water quality program. The bill, know as Public Law 92-500, required all municipal sewage treatment agencies to achieve secondary wastewater treatment by 1977.

In 1974, Gov. Dan Evans chose Metro as the agency responsible for areawide water quality planning for the Green and Cedar River basins. Metro spent most of that year evaluating the agency's policy on treatment levels. In the fall, the Metro Council endorsed a six-point Puget Sound water-quality program that included a decision to provide secondary treatment.

Secondary treatment

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed into law a measure allowing municipal discharges to apply for a waiver of the secondary wastewater-treatment requirement if they could prove that discharge of primary effluent was not harmful. In 1978, Metro applied for waivers to continue primary treatment at its four Puget Sound plants. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) tentatively approved the waiver for the West Point plant in 1981. The state Department of Ecology later agreed with EPA's decision.

Clean Water Act – Environmental Protection Agency

By 1984, however, much public attention focused on Puget Sound water quality and pollution issues, in particular toxicant contamination. Scientists conducted studies of Puget Sound to determine if secondary treatment would be beneficial. The research found increasing levels of toxic materials in the waste stream and in marine life. The studies concluded that secondary treatment, with pretreatment of industrial waste before discharge to sewers, would reduce the levels of toxins in Puget Sound.

EPA and the Ecology Department, after reconsidering the treatment level issue, announced that all treatment plants discharging directly into Puget Sound must provide secondary treatment.

The Ecology Department issued a compliance order that required planning for secondary treatment be completed and design work begun by July 31, 1986. The compliance order required Metro to have secondary facilities operating by early 1991.

In July 1986, the Metro Council adopted a plan to upgrade its Puget Sound plants to secondary treatment. Under the plan, Metro would upgrade its West Point plant to secondary and convert its Alki and Carkeek plants to treat stormwater flows only. The Renton plant has provided secondary treatment since in opened in 1965. The council also approved a plan to demolish the Richmond Beach plant and exchange sewage flows with the City of Edmonds.

In addition, Metro adopted a program to control combined sewer overflows further and achieve a 75 percent reduction in overflows during a 20-year-period to fulfill new state Ecology Department requirements.

In converting West Point from primary to secondary treatment, finished in 1996, Metro reduced the plant size and limited shoreline facilities while improving public access to water and screening the plant from shoreline view.

Toxicant pretreatment

In 1984, Metro finished a five-year study of toxic chemicals in Puget Sound and other regional waters. The Toxicant Pretreatment Planning Study also identified toxicants in Metro's wastewater collection and treatment system. Metro has carried out several study recommendations, including:

- new industrial pretreatment standards

- increased industrial waste monitoring

- a program of recovering costs from industry for monitoring and regulating industrial wastes

- continued support for programs that control toxicant discharge at its source, such as industrial pretreatment, water supply corrosion control, and proper household hazardous waste disposal

In 1987, Metro issued Priorities for Water Quality , an update of the area plan for the Seattle-King County metropolitan region. The update concluded that surface water management and toxicant control deserve further attention.

Biosolids recycling

Biosolids, a nutrient-rich semisolid byproduct of wastewater treatment, became a point of interest for the Metro Council in 1983, when it approved a long-range plan for managing biosolids.

The plan identified three land-application uses--silviculture, soil improvement and reclamation, and composting--for Metro biosolids through the year 2000. Since 1972, Metro had been committed to recycling biosolids, instead of burning it or taking it to a landfill--as done by some other sewer agencies.

The agency sold some biosolids to private companies for creating a compost soil amendment, and it used some in special parks projects to enrich infertile soil. Metro also contracted with the University of Washington to test use of the biosolids on trees at the university's Pack Forest site.

Expanding on the successful silviculture idea, Metro in 1987 began biosolids application on land owned by the Weyerhaeuser Co. and other forest-products companies.

In recognition of the agency's successful biosolids-recycling operation, in October 1988 the U.S. EPA gave Metro an award for operating the nation's best beneficial biosolids-use program. EPA found that Metro biosolids met federal standards for soil enrichment.

And thanks to the agency's industrial pretreatment and hazardous waste education programs, the number of metals and pathogens in biosolids was reduced so significantly that the federal government approved its use for agricultural crops.

Metro also worked with the Northwest Biosolids Management Association and the national Water Environment Federation to provide information to the public about biosolids recycling.

Because of those efforts, Metro biosolids had achieved public acceptance by 1995. Biosolids continues to be used for gardening compost and on Western Washington forests. A major market is in Eastern Washington, where knowledgeable dryland wheat farmers and hops ranchers will use all the biosolids available.

Another aspect of biosolids production also contributes to Metro's recycling efforts. Methane gas produced during the solids digestion process at Metro's West Point plant is used to power the plant's equipment and generate electricity for the City of Seattle power grid. Most methane produced at the South plant in Renton is scrubbed and sold as natural gas to Puget Sound Energy.

Merging with King County

On Nov. 3, 1992, King County voters approved a ballot resolution to merge Metro and King County. On Jan. 1, 1994, Metro joined King County as the Department of Metropolitan Services.

Effective January 1996, Metro's old Water Pollution Control Department, including the wastewater treatment function, became part of the county's new Department of Natural Resources. Metro's old Transit Department became part of the county's new Department of Transportation. And functions of Metro's old Technical Services Department and Finance, Budget and Administration Department merged into the new Natural Resources, Transportation and other county departments.

In 1999, the King County Council approved the Regional Wastewater Services Plan, a 30-year comprehensive program to protect the environment and public health. The plan includes a new treatment facility to serve north King County and south Snohomish County.

In 2018, King County has started work on a new Wastewater Systemwide Comprehensive Plan to take us to and beyond 2030.

Sources

Enabling legislation – as codified in the Revised Code of Washington, Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle (Metro), February 1989

Better than promised: an informal history of the municipality of metropolitan Seattle, Bob Lane, King County Department of Metropolitan Services, 1995

Translate

Translate