Oyster Shell Catch Basin Retrofit, Mercer Island

Using oyster shells to clean up stormwater: a pilot study

When it rains, water runs over roadways, sidewalks, and buildings. On the way, it can pick up pollutants from cars, roofs, pet waste, yard care products, and more. We call this water "stormwater". Stormwater is one of the main ways pollution enters our waterways in the Puget Sound region. Stormwater can have many different types of pollutants. These include heavy metals like copper and zinc. These get into stormwater through sources like cars and roofing materials. These metals can be harmful to fish and other aquatic animals. This is especially true if the water is also low in minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium. Low mineral content is also called low water hardness. Water percolating through the soil can pick up these buffering minerals. But, most urban stormwater isn’t filtered through soil like it would be in a forest. Instead, it enters our waterways through storm drains. Without buffering minerals, heavy metals in stormwater can be particularly toxic. This is true even at low concentrations of heavy metals.

This project tested the effectiveness of treating stormwater with crushed oyster shells. There is evidence to suggest crushed oyster shells remove heavy metals from stormwater. Oyster shells are also natural sources of a buffering mineral, calcium. Calcium can further reduce any harmful impacts from heavy metals to aquatic organisms.

King County partnered with the City of Mercer Island for this work. Funding for this project came from the Stormwater Action Monitoring (SAM) program.

Study findings

King County researchers collected samples during four storms in 2019. These samples came from stormwater in Mercer Island Town Center. The researchers tested if the stormwater was cleaner after passing through oyster shells. Unfortunately, the results showed no consistent reduction in suspended solids or heavy metals. The researchers halted the study in March 2020.

Oyster shells have provided successful stormwater treatment in smaller scale applications. These include treating runoff from parking lots or roofs. The stormwater system at the Mercer Island Town Center is much larger. It’s likely that in this setting the ratio of oyster shells to stormwater was too small. Or the oyster shells were in contact with the stormwater for too short a time. The results suggest that this type of treatment is not likely to be successful in larger systems.

Project documents

Quality assurance project plan

Common challenges in stormwater management:

Cities and counties manage stormwater to reduce impacts on local waterways. One method is to retrofit existing stormwater infrastructure to add stormwater treatment. Identifying retrofit options to fit particular needs can be difficult. There are few non-proprietary options to choose from for some common situations. For example:

- Areas selected for retrofit are generally already built out, with limited above-ground space.

- Typical heavy metals concentrations in urban stormwater are often difficult to treat. They occur within a range that is difficult to reduce through common methods.

- With limited resources, low cost options are more practical for widespread treatment. Low cost considerations include installation and maintenance costs. Widespread installation can treat more stormwater, and have better outcomes for water quality.

Monitoring effectiveness

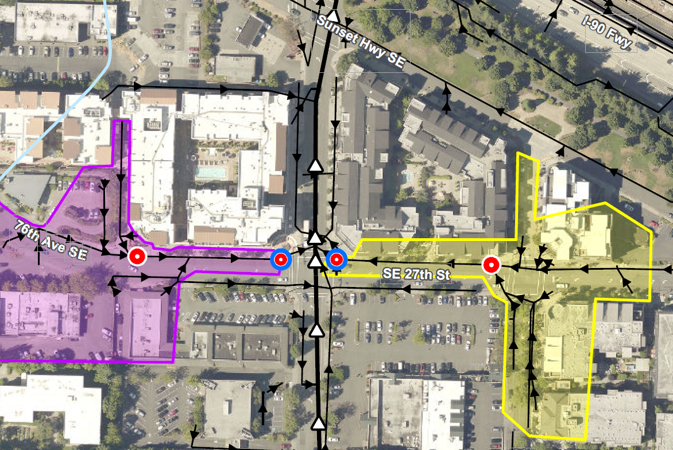

This study took place in the City of Mercer Island Town Center. Researchers retrofitted two storm drains to include oyster shell treatment. These storm drains are also known as catch basins. These basins were partially filled with coarsely crushed oyster shells. They were then fitted with a baffle over the outlet pipe. The baffle slows down the stormwater to increase contact time with the oyster shells. Increasing contact time should increase the potential for treatment. This design could also cause more particulate material to settle out of the stormwater. As a result, pollutants that are often bound to particulates could get trapped in the basins. These pollutants include bacteria and petroleum chemicals.

Technical project objectives

- Collect time-weighted composite stormwater samples for 10 discrete storms over two wet seasons. Collect from the inlet and outlet of four catch basins. Two basins will have oyster shell retrofits, and two will not. Analyze the samples for:

- total and dissolved metals

- total suspended solids (TSS)

- total organic carbon (TOC)

- dissolved organic carbon (DOC)

- total and dissolved phosphorus

- total nitrogen

- hardness

- pH

- flow

- Calculate changes in concentrations between influent and effluent samples. Calculate this change for each catch basin and each storm.

- Check effectiveness of oyster shell retrofits. Check dissolved metals treatment and phosphorus treatment to test effectiveness. Compare the data collected from this pilot effort with the TAPE performance goals.

- Compare “treated” catch basin effluent dissolved metals concentrations to freshwater quality standards.

- Test whether “treated” catch basins reduce pollutants more than “untreated” catch basins. This will only consider the pollutants analyzed in this study.

- Measure solids accumulation in “untreated” catch basins over the study timeframe. Observe whether oyster shell retrofits interfere with solids retention.

- Test the relationship between solids accumulation and pollutant removal in “untreated” catch basins. This will support future evaluation of the current threshold for catch basin maintenance.

- Communicate results with interested parties, including municipal stormwater permittees.

Team members

The project team consists of:

- Personnel from King County’s Water and Land Resources Division. King County team members include:

- Scientists from the Science and Technical Services Section

- Scientists from the King County Environmental Laboratory

- Partners from the City of Mercer Island

- A SAM coordinator from Washington State Department of Ecology.

- The Port of Seattle, who provided:

- the initial retrofit design

- the oyster shells for this pilot project

King County coordinated with the City of Mercer Island for the project signage. Support for the interpretive signage on the project utility boxes came from:

- The King County Information Technology Design and Civic Engagement team.

Partners

City of Mercer Island – Public Works/Stormwater Utility

Washington State Department of Ecology

Port of Seattle – Maritime Stormwater Program

Project schedule

Sampling project plan: March 2019

Retrofit installation: March 2019

Field investigation: April 2019 through September 2020

Final report: End of 2021

Translate

Translate