King County study of Lake Washington sediment shows decline in once-common dangerous chemicals, offering a roadmap to address newer health risks

Summary

King County researchers studying sediment from the bottom of Lake Washington found levels of PCBs dramatically declined once the widely used toxics were banned more than 50 years ago – giving hope that ending the use of other harmful chemicals will lead to a healthier environment for people and fish and wildlife.

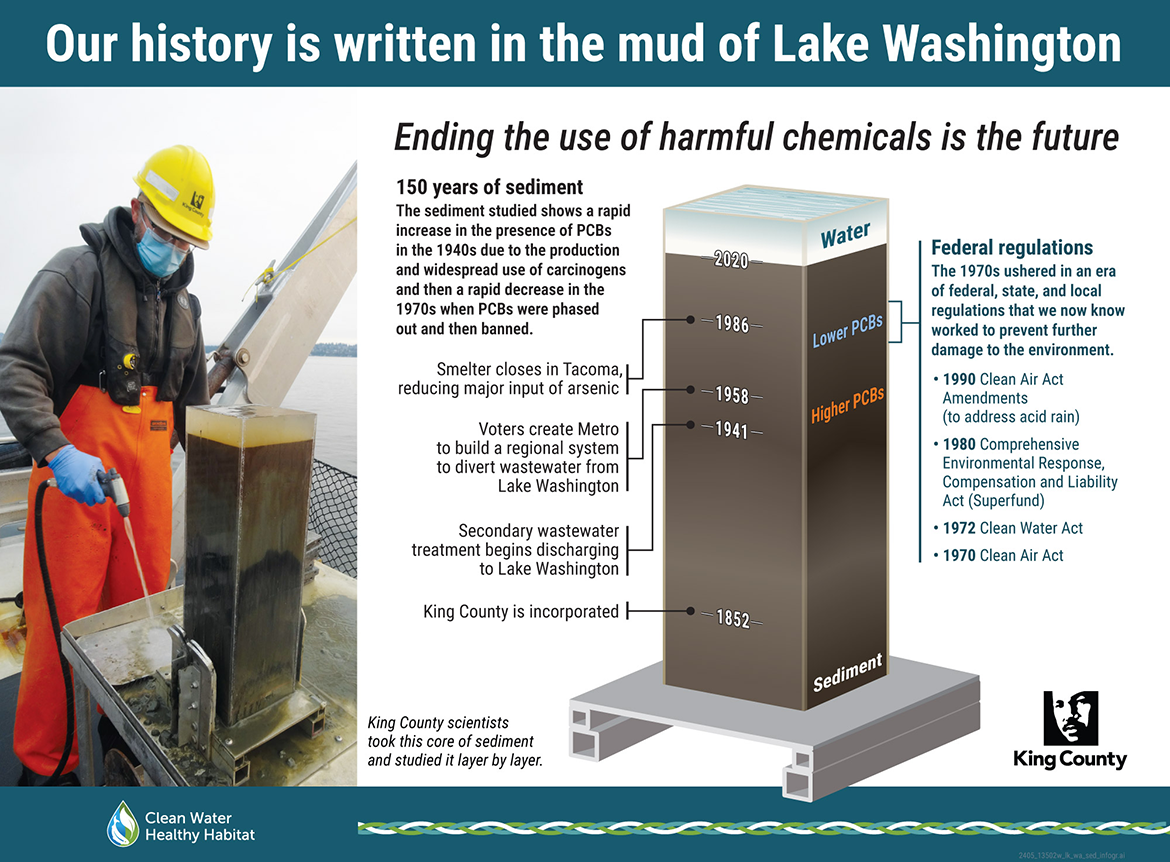

Our history is written in the mud of Lake Washington

Ending the use of harmful chemicals is the future

150 years of sediment

The sediment studied shows a rapid increase in the presence of PCBs in the 1940s due to the production and widespread use of carcinogens and then a rapid decrease in the 1970s when PCBs were phased out and then banned.

Sediment layers

King county took this core of sediment and studied it layer by layer.

- 1986: smelter closes in Tacoma, reducing major input of arsenic

- 1958: voters create Metro to build a regional system to divert wastewater from Lake Washington

- 1941: Secondary wastewater treatment begins discharging to Lake Washington

- 1852: King County is incorporated

Federal regulations

The 1970s ushered in an era of federal, state, and local regulations that we now know worked to prevent further damage to the environment.

- 1990: Clean Water Act amendments (to address acid rain)

- 1980: Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (Superfund law)

- 1972: Clean Water Act

- 1970: Clean Air Act

News

A King County study of Lake Washington’s lakebed sediment shows levels of PCBs, the once common and dangerous chemical are expected to fall below currently detectable levels within the next two decades. Researchers say the findings reaffirm the effectiveness of regulations and personal actions and offer a strategy for addressing emerging environmental threats, including stormwater pollution.

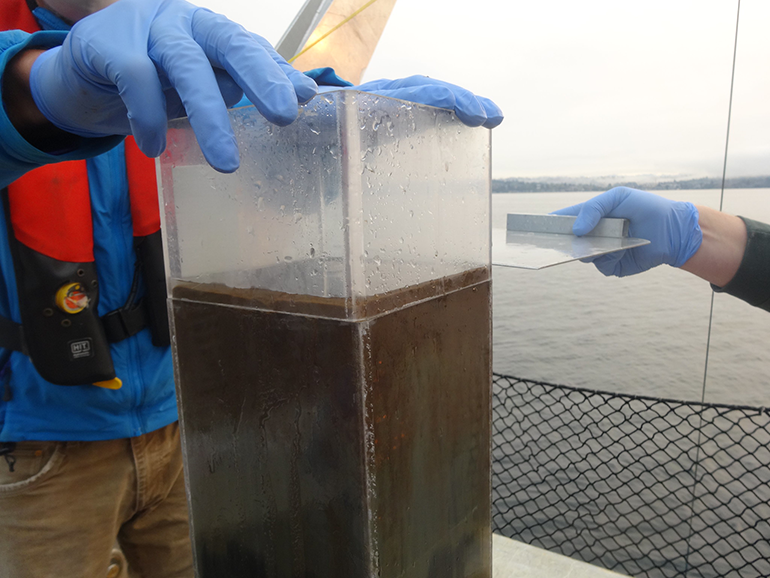

The pilot study, including lakebed coring conducted by scientists aboard the King County research vessel SoundGuardian, also showed how the techniques for collecting and analyzing samples could be used in other research projects to detect human-caused changes in environmental conditions.

Reducing toxic chemicals in the environment is one of the key goals of King County’s Clean Water Healthy Habitat, Executive Dow Constantine’s initiative to produce better results faster for people, salmon, and orcas.

“The research conducted by our scientists on the sediment layers beneath Lake Washington sends an unmistakable message: The best way to protect people, fish, and wildlife from harmful chemicals is to stop their production and use," said Executive Constantine. "A century from now, those layers will show whether we acted to safeguard future generations from toxic 'forever chemicals.' Let’s make sure our legacy reflects progress.”

At almost 16 inches long and taken from the bottom of Lake Washington in nearly 200 feet of water near the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge, the muddy sediment core spans more than 150 years of history.

The core reveals deposits of materials from both natural and human sources, including metals, PCBs, and other matter that settled onto the lakebed from the water and atmosphere. The sample material was taken to the King County Environmental Laboratory in Fremont for analysis.

Testing revealed a rapid increase in sediment PCB concentrations beginning in the 1940s until the 1970s, closely tracking production and widespread use of the highly carcinogenic material.

Those PCB concentrations in the sediment decreased rapidly after the phase-out of their production and a final national ban in the 1970s. Researchers believe that if the current rates of recovery continue, sediment PCB concentrations on the lakebed surface could fall below the threshold for laboratory quantification in the next 20 years.

“Looking specifically at PCB levels, our research shows how regulatory actions can stop ongoing contamination and allow lake sediments to improve over time,” said Josh Latterell, who leads King County’s Science Section at the Department of Natural Resources and Parks. “Many of today’s ‘forever chemicals,’ like PFAS, are found widely in consumer products, and both regulations and consumer choice are part of the solution.”

Other dangerous chemical levels have also steadily decreased since their peaks in the 20th century. Inputs of cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, and nickel into Lake Washington peaked near the middle to the early second half of the 20th century.

If recent trends continue, researchers believe sediment concentrations of these metals on the very top of the lakebed could reach predevelopment background levels in the next 30 to 40 years – even sooner for mercury.

Concentrations of some metals remain elevated in the bottom mud of Lake Washington, including copper and zinc, which researchers believe continue to enter the lake’s watershed from a variety of sources. Copper may originate from vehicle brake dust and tires, as well as roofing and treated lumber. Other sources of zinc include galvanized materials such as siding and fencing, and moss control products.

A generational snapshot of the health of Lake Washington

The study provides a generational snapshot of the health of Lake Washington, which until the 1960s received untreated wastewater and was polluted by other sources from the growing lakeside communities.

Metro was established in 1958 with the mission to divert sewage from the lake. Between 1963 and 1968, more than 100 miles of large trunk lines and interceptors were installed to carry sewage to West Point Treatment Plant in Seattle and South Treatment Plant in Renton.

The Lake Washington basin is home to 20% of the state’s population and while sediment contaminant concentrations have fallen, more work needs to be done – especially with preventing toxic pollution from getting into our environment and filtering pollution from stormwater runoff.

While there are still fish consumption advisories for PCBs, PFAS, and mercury, the sediment core results offer hope that community and regulatory actions in the coming decades can continue to make progress toward safer fish to eat.

“Lake sediments are natural archives recording changing conditions over long periods of time, and the success of our Lake Washington sediment coring pilot study demonstrates we can rely on this method to evaluate water quality trends and detect human-caused changes,” said Beth LeDoux, Supervisor for King County’s Lakes, Streams, Sound, and Ground Unit.

King County’s Science Section is a unit of the Department of Natural Resources and Parks, one of the nation’s largest metropolitan natural resource agencies.

“Our scientists provided an insightful view of our region’s history that can shape a healthier future for Lake Washington,” said John Taylor, Director of the Department of Natural Resources and Parks. “Their scientific findings confirm that effective regulations and personal actions can protect people, fish, and wildlife from harmful chemicals. Let’s apply those same principles to confront the latest threats to water quality from chemical manufacturers.”

The research conducted by our scientists on the sediment layers beneath Lake Washington sends an unmistakable message: The best way to protect people, fish, and wildlife from harmful chemicals is to stop their production and use. A century from now, those layers will show whether we acted to safeguard future generations from toxic 'forever chemicals.' Let’s make sure our legacy reflects progress.

Our scientists provided an insightful view of our region’s history that can shape a healthier future for Lake Washington. Their scientific findings confirm that effective regulations and personal actions can protect people, fish, and wildlife from harmful chemicals. Let’s apply those same principles to confront the latest threats to water quality from chemical manufacturers.

Looking specifically at PCB levels, our research shows how regulatory actions can stop ongoing contamination and allow lake sediments to improve over time. Many of today’s ‘forever chemicals,’ like PFAS, are found widely in consumer products, and both regulations and consumer choice are part of the solution.

Lake sediments are natural archives recording changing conditions over long periods of time, and the success of our Lake Washington sediment coring pilot study demonstrates we can rely on this method to evaluate water quality trends and detect human-caused changes.

Contact

Saffa Bardaro, Department of Natural Resources and Parks, 206-477-4610

Translate

Translate